Given the particulars in his History, we may wonder how he was able to recall the details enlivening his account. By contrast, even when Casanova names sexual acts euphemistically, he offers details that render his experiences apprehensible, and rarely does he urge the reader’s imagination to wander freely. In this suggestive scene, a chaperone bares a model’s breasts while the painter raises her skirt with his maulstick. 1770-1773) invites viewers to project on a blank canvas their imagined endings to a preliminary encounter. “Those who think I lay on too much color when I describe certain amorous adventures in detail will be wrong, unless, that is, they consider me a bad painter altogether.” His tell-all manner sets him apart from an artist like Jean-Honoré Fragonard, whose The New Model (c. He calls himself a painter, coloring his textual tableaux with emotion and rendering them in striking detail. Like a novelist, Casanova weaves complicated plots involving obstacles to overcome, deals to be made, revenge, skullduggery, and coincidence. Though often highly charged with eroticism, the “adult” content of such images tended to be lyrical, allusive or playful, leaving more to the imagination than Casanova’s exuberantly explicit accounts of his venereal exploits. The pictorial genres most associated with amatory subjects range from myth, allegory and pastoral to so-called boudoir scenes and voyeuristic vignettes.

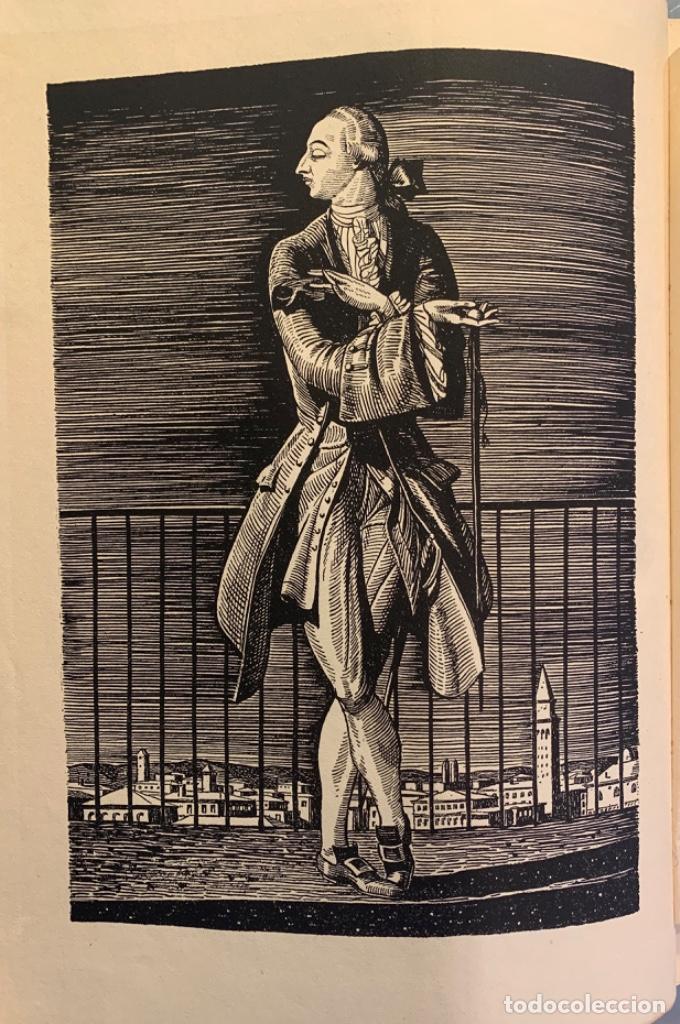

The Seduction of Europe-also drew on these concepts and practices in works that explored the amorous and erotic life of the eighteenth century. Artists who were Casanova’s contemporaries-many of whom figure in the exhibition Casanova. Their frequency and diversity set Casanova apart from contemporaries, yet his experiences exemplify concepts and practices current during his life, and he draws on a well of shared convention in representing them. Affairs numbering well over one hundred enliven the History of My Life. His amorous adventures begin at the tender age of eleven, and by story’s end he has experienced every feeling associated with love from intense longing to painful despair. As the hero of the memoirs he started writing in 1789, when he was sixty-four and living in exile in Bohemia, Casanova performs as ardent lover, callous libertine, amiable friend, and suitor wronged. In all its splendor and misery, love dominates the life of Giacomo Casanova (1725-1798). We are grateful to Keith Luria and Melissa Hyde for making final revisions to the essay and for permitting us to publish it in Journal18. The essay is yet another testament to Mary’s unique talent for bringing eighteenth-century art to life and for making us think about it in a new way, as well as her own seductive powers of analysis and wordplay. We wanted to publish it in Journal18 so that her vivid insights into Casanova’s libertine text and like-minded artworks could be shared with our scholarly community. Due to late changes in the exhibition’s checklist, however, Mary’s essay did not appear in the catalogue. This explains the choices behind some of the artworks she discusses. She originally wrote it for the catalogue to the exhibition Casanova: The Seduction of Europe, connecting paintings in the show with episodes from Casanova’s erotic intrigues. Among her last essays was a playful and erudite encounter with Casanova’s memoirs, seen through the prism of eighteenth-century European painting. Sheriff, one of the most brilliant and beloved scholars of eighteenth-century European art, died on October 19, 2016.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)